Development of a rating scale for a spoken English end of course test for Italian middle school students

The assessment of oral skills is often seen as difficult, especially in low stakes contexts (Alderson and Clapham 1995). This paper sets out to examine a way of ameliorating the validity and reliability of these tests by the development of a rating scale for an end of year oral English test in the third and final year of a middle school in the North of Italy.

The paper examines areas relating to the institutional background, what to look for in oral tests, mechanisms for rating test performance, and the age factor. It then goes on to develop a rating scale to be used in this context, analysing factors such as validity and reliability. The paper then analysis the results quantitatively and qualitatively, by seeking the views of the testers. The conclusion discusses ways to further improve the tests and scale in future years.

CHRISTOPHER ALTON BALDWIN

TYL ASSIGNMENT

Development of a rating scale for a spoken English end of course test for Italian middle school students

MSc/Diploma in TESOL, English Studies, Aston University

JUNE 2006

Development of a rating scale for a spoken English end of course test for Italian middle school students Introduction The assessment of oral skills is often seen as difficult, especially in low stakes contexts (Alderson and Clapham 1995). This paper sets out to examine a way of ameliorating the validity and reliability of these tests by the development of a rating scale for an end of year oral English test in the third and final year of a middle school in the North of Italy.

The paper examines areas relating to the institutional background, what to look for in oral tests, mechanisms for rating test performance, and the age factor. It then goes on to develop a rating scale to be used in this context, analysing factors such as validity and reliability. The paper then analysis the results quantitatively and qualitatively, by seeking the views of the testers. The conclusion discusses ways to further improve the tests and scale in future years.

Background

The 78 students in this study are 12-13 years old, and have been studying English for at least 3 years, and many for 8 years. The English course consists of two hours a week with an non-native speaking English teacher, focusing on grammar, reading and writing, and one hour a week with a native speaking teacher, following a task-based communicative syllabus, called the “Spoken English” (Inglese Parlato) course, in small groups of 5-10 students. These groups are streamed according to ability. At the end of the course 5 students from each of the 3 classes (15 in total) judged the most able are entered for the Cambridge ESOL KET examination, whilst the other students may choose to sit the FLYERS exam, with 27 students choosing to do so this year.

This study will focus on the end of course assessment of the spoken English course. The institution requires a grade to be given to each student on the following scale:

1.Poor 2.Fair 3.Good 4.Very good 5.Excellent

Poor is considered a “fail”, and all the other scores are “pass”. Grades of “poor” for a student in many subjects could mean that a student would be required to repeat the entire year of schooling. In previous years, the grades were given according to the subjective opinion of the teacher after an oral interview. This leads to problems of interrater reliability (Turner & Upshur 2002, Upshur and Turner 1999, Knight 1992:294), intrarater variation (Alderson and Clapham 1995:186) and rater bias (McNamara and Adams 1991/1994 and Linacre 1989–1993, both cited in Upshur and Turner 1999).

There were three teachers working on these courses, each with three groups. Near the end of the course one of the teachers went on maternity leave, requiring the tests to be carried out by two substitute teachers who did not know the students. One of these teachers was a novice teacher, with no experience of testing.

How to give grades?

It is often noted in the literature that oral tests are seen of as being difficult to perform, especially in low stakes contexts by inexperienced testers (see Knight 1992, Alderson and Clapham 1995). The first aspect to look at is that is what aspects of oral behaviour to look for in the test. Knight (ibid:295-6) lists the following aspects of oral competence which can be assessed:

GRAMMAR VOCABULARY PRONUNCIATION FLUENCY CONSERVATIONAL SKILL SOCIOLINGUISTIC SKILL NON-VERBAL CONTENT

These points then need to be examined for inclusion or rejection in a particular context, taking into account the age of the students, the level and the course content, and then weighted, to assign greater or lesser importance to various aspects. One way of weighting these points is by using a scale.

Scales usually take the form of:

. . . a series of short descriptions of different levels of language ability. The purpose of the scale is to describe briefly what the typical learner at each level can do, so that it is easier for the assessor to decide what level or score to give each learner in a test. The rating scale therefore offers the assessor a series of prepared descriptions, and she then picks the one which best fits each learner (Underhill 1987: 98 cited in Upshur and Turner 1995:4).

North and Schneider (1998:221) describe five different methodologies for scale development, each of which could be appropriate for different situations, provided that ‘care is taken in the development’ of the scales. This highlights the danger of using scales imported from other settings. To ensure validity a scale must represent the actual abilities of the students, not just what the theory says (Fulcher 1987:291). This implies the need for an empirically derived scale, based on observed student performance.

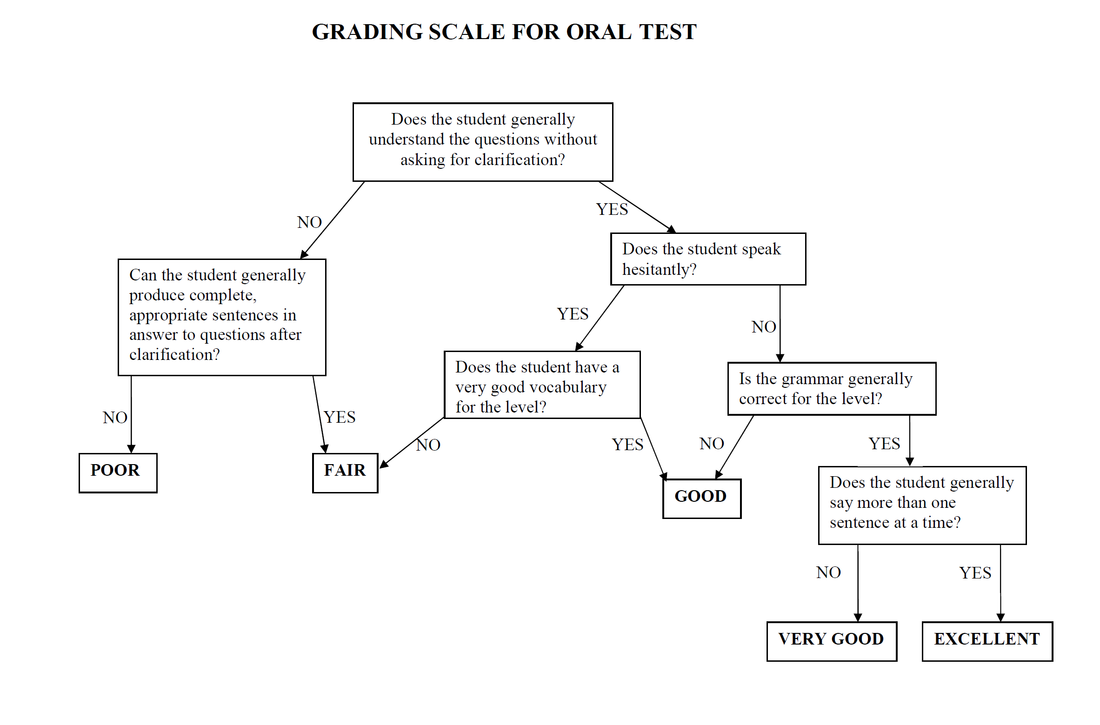

An Empirically derived, binary choice, boundary definition (EBB, Upshur and Turner, 1995) scale is one way of avoiding some of the problems of reliability and validity. This type of scale examines the observed features of student performance, and develops YES/NO questions (hence binary choice) to divide the group into two, then sub-divide, until the final grades are obtained (see appendix 1). This is ‘boundary definition’ as it describes the boundaries between grades and not the mid-point of a grade, as in a traditional scale. This has the advantage of making it easier to categorise the performance if it seems to fall between two grades. Construct validity is built in as the scale is derived from the observed performance.

The age factor

Many existing scales of oral language competence bear “little resemblance to the lives of lower secondary school pupils, and the areas of their foreign language use” (Hasselgren 2003:13). It is therefore important to develop a scale which takes into account the real abilities and language uses of the students and that is based on concepts appropriate for the age.

Hasselgren (2003:14-16) describes a survey of 13-15 year-olds to find out “where they use their [English], who with, why, and what they talk about.” This study reports that these young learners use English in class, talk to friends, give directions to tourists, chat on the internet and use English on holiday. Although not all students in the Italian context use English to the extent implied by Hasselgren in Norway, it is vital to take into account the language that the students actually use, to make sure that the scale does not look for things that teenagers simply do not do, in order to maintain validity. Rea-Dickins (2000:248) talks about the ‘appropriacy of procedures for the age range of the learners, their motivation and interests, and their levels of language proficiency’ as being important factors in testing.

Skehan (1998 cited in Elder et al 2002:349) talks about factors affecting test task difficulty. These include:

code complexity: incorporating both linguistic complexity/ variety and vocabulary load/variety; cognitive complexity: involving cognitive processing factors such as information type and organizational structure as well as the familiarity of task topic discourse and genre. (Skehan, ibid:349)

These factors need to be overcome for adult learners as their proficiency increases, but they present particular challenges for younger learners. On cognitive complexity, we cannot expect young learners to operate at adult levels. According to Piagetian theory children around the age of 12 enter into the ‘formal operational period’ where abstract and hypothetical thinking becomes possible (Das Gupta 1994:46), although Vygotsky argued that age is not a factor, placing more importance on social context (see Oates and Grayson 2004:17). If there are fundamental changes in the cognitive abilities of children taking place at this age, it would be invalid to look for factors above the cognitive ability of the child in the test.

This then has an impact on the ‘code complexity’ factor of test difficulty. If children are not able to operate cognitively at a certain level, or they have only just begun to do so, they will not be able to produce or comprehend language at that level, or they have very little experience of doing so even in L1, then they will certainly lack the experience to be able to communicate at this level in L2.

Another aspect to consider is the student’s desire to perform well in tests. The grade achieved could bring about important positive or negative consequences for the child, such as parent approval/displeasure, which could bring about stress, which could in turn negatively affect test performance. This is needs to be balanced with Rosenberg’s (1979 cited in Miell 1995:205) observation that as children pass into adolescence they place less weight on the opinions of adults, for example teachers and parents, and more weight on judgments of their peers.

Thus in classes where there are low achievers who are liked by their peers there could be a tendency to want to perform badly in tests, or conversely, if there are positive peer influences in the class this could positively add to the desire to please parents and teachers and thus perform well in tests.

The research

All of the above factors need to be born in mind when designing tests and rating scales for students of this age group. Considering these points, it was decided to develop an EBB scale, using the following procedure, based on the model of Upshur and Turner (1995:6-7):

Students of all levels were observed during a two week period during lessons to develop YES/NO questions to divide them into an “upper-half or lower-half” (Upshur and Turner, ibid). These groups were then observed to develop questions to sub-divide them into the score categories required by the institution. The scale thus produced was shown to teachers experienced with this age group, level and grading system to get feedback and modify the questions. The modified scale was then piloted in lessons with groups from all three levels by speaking informally to students and comparing the grade obtained with an impressionistic judgement of the student’s ability. The scales were distributed to the teachers who would be conducting the tests, the EBB system was explained and their opinions were sought on the questions. Feedback was used to modify some of the wording of the questions. The teachers using the scales were then given the final version of the scale, and were shown how to use it. The novice teacher also observed a mock test and was helped afterwards to grade the student using the scale. She also received training on how to conduct oral tests.

See appendix 1 for the complete scale.

Many of these steps require impressionistic judgement (see also Upshur and Turner, ibid) but North and Schneider (1998:220) make the point that in a low stakes context where the students are known to the testers an intuitive approach can be appropriate. They go on to criticise Upshur and Turner (1995) stating that

such an approach is only likely to be successful in one specific, limited

context (North and Schneider 1998:222)

This scale has, however, been developed for this one specific context.

The tests themselves were a traditional interview type with one student and one teacher, as described by Lowe (1982, cited in Shohamy et al 1986:215). This is the standard method for tests of all subjects in the school. See below for a discussion of how validity was maintained within this testing format.

After the tests were carried out the results were compiled for analysis and the teachers were interviewed to gauge their opinions on the value of the scale.

Discussion of the scale

Holistic scale

A holistic scale, that is one which combines all aspects of linguistic competence into one scale, was chosen for this project for two different reasons:

A holistic approach allows us to grade the observed results, without trying to give a grade to an unobservable mental process, such as grammatical ability, which cannot be manifested apart from other communicative aspects. (Knight, 1992:300) The use of a single scale is much more practical in a busy classroom, where the teacher has many students to rate, and not much thinking time between tests. (Hasselgren, 2003:21)

Shohamy et al (1986:219) give an example of a holistic scale, encompassing many areas of communicative competence in one scale. Their scale uses very wide bands, appropriate for a whole population, but in a limited context it can easily produce a ‘bunching up’ effect (Fulcher 1987:288), where most students receive the same grade. In this context finer degrees of distinction are necessary, as there are smaller differences between the levels of the students, the minimum here being a weak A1 to a maximum of B1 on the council of Europe scale, thus with this scale only 3 grades would be used to describe all the students.

Validity

The holistic scale allows different aspects of communicative ability to be given different levels of importance, and thus lead to different grades, reflecting Matthews’ observation that it is

illogical to allocate equal marks for the various sub-skills as if the relationship between them was a simple one of addition. (Matthews 1990:118)

This is an important aspect in the validity of the scale. The scale must represent what was actually taught on the course in order to be valid, with the more basic areas of communicative ability being lower down on the scale, for example the questions which lead to “poor” (grade 1) here test the student’s basic comprehension, and basic ability to form a reply. These were fundamental aspects of the course, so “no” to both of these should lead to a fail. Looking at the higher grades, the distinction between “fair” and “good” (grades 2 and 3) is based on vocabulary range, which was an important part of the course. Grammar only features at the higher end of the scale as the course was communicative, not grammar based, but an effort was made with the higher level groups to correct grammatical errors. This reflects a greater weight being given to fluency than accuracy in Brumfit’s (1984) accuracy/fluency dichotomy, which is valid for a test of an oral course.

Consultation with teachers during construction of the scale also leaded to greater validity and reliability from the point of view of those who used the scale.

Motivation is also a key factor for young learners, so the scale should not be too severe, as low grades could reduce motivation, and high grades increase motivation. This is important in this context as most of the students will go on to study English at high school, so a realistic yet positive image of their abilities will help them with the harder work to come at high school.

To maintain validity within the interview type test, the format of the test included questions and subjects that the students were familiar with. The interview was conducted in a style similar to the KET/FLYERS oral exam interviews (UCLES 2002, 2003) as an important factor in the validity of these tests is that they help prepare the students for the high stakes exams that they may sit in the future. Validity is also maintained by administering a familiar type of test. As the students are interviewed for all their school subjects, this is less stressful than an unfamiliar type of test. ‘Affective factors’ (McNamara 1996: 86 cited in O’Sullivan 2002:278) and student personality, such as shyness can play a large part in performances, so an effort was also made to help shy students feel more comfortable, so as not to negatively affect their performances (Crozier and Hostettler, 2003).

Reliability

Many of the questions could be considered rather ambiguous, so this requires a certain amount of discernment on the part of the testers, and agreement between testers as to what exactly the questions mean, in line with Upshur and Turner’s (1995:9) comment that

developing consensus on the precise meanings of the terms used in the scales is an integral part of the scale development procedure.

This highlights the importance of tester training, to ensure interrater and intrarater reliability. Lunz et al (1990, cited in Upshur and Turner, 1999) observe that training can improve intrarater consistency, although it is difficult to make different raters equally severe. Chalhoub-Deville and Wigglesworth (2005), however, report remarkable consistency worldwide across testers. Matthews (1990) mentions the use of standardization meetings using video, although this may not be appropriate in a low stakes context, where the teachers already have a very heavy work load.

Results

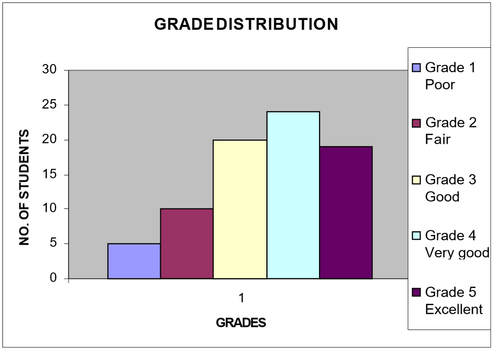

See appendix 2 for a detailed table of all the results. Figure 1 shows the distribution of grades for all the groups. Here we see a normal distribution, but with the mean grade, 3.5, being lower than the median and mode (both 4). This implies from a purely statistical point of view that the scale produces too high grades, or that the raters were overly lenient, as a perfect normal distribution would produce a mean, median and mode of 3. This, however, needs to be balanced with the context. The lowest grade “poor” is generally reserved for those students who do not show any desire to learn English, and who have a non-existent or very low ability. The next grade up “fair” rewards those students who apply themselves to the course with a pass, even though their ability level is still relatively low. A grade of “very good” would indicate a level of A2 (on the Council of Europe global scale), equivalent to the KET and FLYERS exams sat by approximately half the students. Thus this grade distribution is appropriate for this context and gives evidence for the construct validity of the test and the scale (Schlichting and Spelberg2003:255)

Interrater reliability

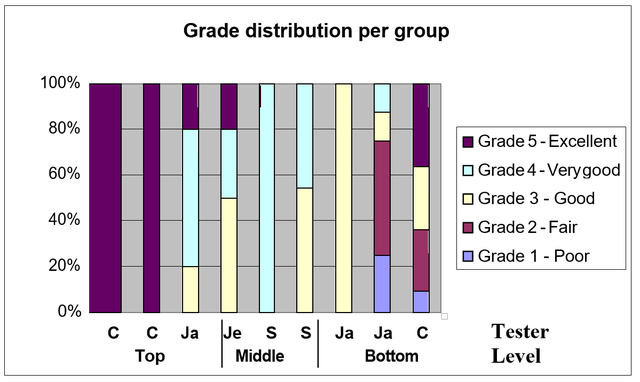

One of the aims of this study was to improve interrater reliability. Figure 2 shows the grade distribution per group and tester. The top groups show 100% of students being awarded grade 5 from teacher C, but a more even distribution of grades from teacher Ja. Ja reported behaviour problems with this group, whilst C had a very good relationship with both of his groups. This could, therefore be a sign of tester bias, or could be a real difference in the ability of the groups, with the poor behaviour being caused by a lack of ability, or a lack of ability leading to behavioural problems. The top groups all sat the KET exam, so the results (unavailable at time of writing) could provide independent evidence for this. The bottom groups show a more even distribution of grades between the raters, but C is still more generous than Ja, providing more evidence for a disparity of standards between raters.

The middle groups here were tested by supply teachers who did not know the students, thus removing the possibility of bias. Here we see a more even distribution, with the novice teacher (Je) producing similar results to the experienced teacher (S), thus providing evidence for the reliability of the scale.

Observations from the testers

During the development of the scale the opinions of experienced teachers were sought to help refine the questions. Most of the reactions were positive, with teachers saying that they thought that it would be useful to have a standardization tool to improve interrater consistency. One teacher (not a tester on these courses) felt challenged by the idea of using a scale, finding it difficult to accept the positions of the questions on the scale, for example assigning greater importance to grammar. She also admitted to preferring to give grades based on her own opinion of the student and whether or not she liked the student. She finally agreed that a scale of some sort is probably a good idea in order to remove these biases.

The testers were all interviewed informally after the tests to gauge their opinions of the scale. All of them said that they found it to be helpful, and that it generally fitted in with their opinions. This could be a sign that the questions are too ambiguous, and can be interpreted very loosely. One of the experienced raters who knew the students, however, reported finding the ‘hesitation’ question too severe, leading to a grade which was too low for the student, especially for lower level groups, and admitted to not following the scale completely for all students. The novice teacher reported that at first she stuck very rigidly to the scale, reading it carefully after each test, then when she felt more comfortable with the procedure she was able to judge more easily herself, using the scale as a guide. This highlights the potential value of such a scale in tester training.

Conclusions

This study has looked at a mechanism of improving the validity and reliability of the grades for a spoken English end of course test. This is the first time that these aspects have been examined systematically in this context, so it is difficult to say if any improvement has been made over previous years, although the results are satisfactory. This study should be seen as the first step in a process of examining these issues in the coming years, trying to implement further improvements.

Further improvements

The first aspect to consider is that of better rater training, both in terms of implementation of tests and standardization of grading, perhaps with standardization meetings being held before the exam period starts to discuss the level of each grade. The questions in the scale could also be reviewed next year with all testers, especially with regard to the criticism of the ‘hesitation’ question noted above, to come to a consensus as to the best questions to use. This could be particularly useful now that the testers are experienced with the rating scale system, and these questions in particular.

The interview test format is greatly criticised by Upshur and Turner (1999), on the grounds that the interview is an unequal social encounter, it does not produce natural language, and has an asymmetry of goal orientation and reactiveness, although students in Shohamy et al (1986)’s study favoured the interview test over other types. The literature gives many examples of other test formats which could in the future be used to further improve validity and reliability, for example:

continuous assessment, such as portfolios (Nihlen and Gardenkrans, 1997 (cited in Rea- Dickins, 2000) Hasselgren, 2003, Council of Europe, 2000) tests taken in pairs (O’Sullivan 2002) role plays (Kormos 1999), although they would need to be appropriate to the age of the students, perhaps using situations such as those described by Hasselgren (2003:14-17) allowing opportunities for student-student scaffolding during and before tests (Mattos 2000)

This research has proved to be valuable as an exercise in the improvement of validity and reliability in the grades assigned to test performances in a low stakes context, which could also be of use to other teachers in similar contexts, to help to encourage teachers and programme coordinators to produce systematic and accurate grades for their students.

Chris Baldwin June 2006

Words: 3792

References

Alderson C. and Clapham C. 1995. Assessing Student Performance in the ESL Classroom J.

TESOL Quarterly 29/1

Brumfit, C.J. 1984: Communicative methodology in language teaching: the roles of fluency and accuracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chalhoub-Deville, M. and Wigglesworth, G. 2005. Rater judgment and English language speaking proficiency. World Englishes, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 383–391, 2005.

Council of Europe. 2000. European Language Portfolio. Strasbourg: Council of Europe and Perugia: Ufficio Scolastico Regione Umbria

Crozier, W.R. and Hostettler, K. 2003. The influence of shyness on children’s test performance.

British Journal of Educational Psychology (2003), 73, 317–328

Das Gupta, P. 1994. Piaget’s theory of intellectual development. In Oates, J. (Ed.), The foundations of child development. Oxford: Blackwell, The Open University Press

Elder, C., Iwashita, N. and McNamara, T. 2002. Estimating the difficulty of oral proficiency tasks: what does the test-taker have to offer? Language Testing 2002 19 (4) 347–368

Fulcher, G. 1987. Tests of oral performance: the need for data-based criteria. ELT Journal Volume 41/4 October 1987

Hasselgren, A. 2000. The assessment of the English ability of young learners in Norwegian schools: an innovative approach. Language Testing 2000 17 (2) 261–277

Hasselgren, A. 2003. Bergen ‘Can Do’ project. European Centre for Modern Languages: Council of Europe Publishing

Knight, B. 1992. Assessing speaking skills:. A workshop for teacher development. ELT Journal Volume 46/3 July 1992

Kormos, J. 1999. Simulating conversations in oral proficiency assessment: a conversation analysis of role plays and non-scripted interviews in language exams. Language Testing 1999 16 (2) 163–188

Linacre, J.M. 1989–1993: Many-facet Rasch measurement. Chicago, IL: MESA Press.

Lowe, P. Jr. 1980 (rev. 1982). ‘Manual for LS Interview Workshops.’ Washington, DC: CIA Language School (mimeo).

Lunz, M.E., Wright, B.D. and Linacre, J.M. 1990: Measuring the impact of judge severity on examination scores. Applied Measurement in Education 3, 331–45.

Matthews, M. 1990. The measurement of productive skills: doubts concerning the assessment criteria of certain public examinations. ELT Journal Volume 44/2, 117-121

Mattos, A.M.A. 2000. A Vygotskian approach to evaluation in foreign language learning contexts

ELT Journal Volume 54/4, 335-345

McNamara, T.F. and Adams, R.J. 1991/1994: Exploring rater characteristics with Rasch techniques. In Selected papers of the 13th Language Testing Research Colloquium (LTRC). Princeton, NJ: ETS (ERIC Document Reproduction Service ED 345 498)

Miell, D. 1995. Developing a sense of self. In Barnes, P. (Ed.) Personal, social and emotional development of children. Oxford: Blackwell and The Open University Press

Nihlen, C. and Gardenkrans, L. 1997: My portfolio collection. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell. North, B. and Schneider, G 1998. Scaling descriptors for language proficiency scales. Language

Testing 15 (2) 217–263

Oates, J. and Grayson, A. 2004. Introduction: perspectives on cognition and language development. In Oates, J. and Grayson, A. (Eds.) Cognitive and language development in children. Oxford: Blackwell and The Open University Press

O’Sullivan, B. 2002. Learner acquaintanceship and oral proficiency test pair-task performance.

Language Testing 2002 19 (3) 277–295

Rea-Dickins, P. 2000. Current research and professional practice: reports of work in progress into the assessment of young language learners. Language Testing 2000 17 (2) 245–249

Rosenburg, M. 1979. Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books

Schlichting, J.E.P.T. and Spelberg, H.C.L. 2003. A test for measuring syntactic development in young children. Language Testing 2003 20 (3) 241–266

Shohamy, E., Reves, T. and Bejarano, J. 1986. Introducing a new comprehensive test of oral proficiency. ELT Journal Volume 40/3 July 1986

Skehan, P. 1998: A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Turner, C.E. and Upshur, J.A. 2002. Rating Scales Derived From Student Samples: Effects of the

Scale Maker and the Student Sample on Scale Content and Student Scores. TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 36, No. 1, Spring 2002

UCLES. 2002. Cambridge Young Learners English Tests Handbook. Cambridge: University of Cambridge ESOL examinations

UCLES. 2003. Key English Test Handbook. Cambridge: University of Cambridge ESOL examinations

Underhill, N. 1987. Testing Spoken Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Upshur, J.A. and Turner, C.E. 1995. Constructing rating scales for second language tests. ELT

Journal Volume 49/1 January 1995

Upshur, J.A. and Turner, C.E. 1999. Systematic effects in the rating of second-language speaking ability: test method and learner discourse. Language Testing 1999 16 (1) 82–111

GRADING SCALE FOR ORAL TEST

| tyl_project.pdf |